The Advantages of the Religious State

By Saint Alphonsus de Liguori

In heaven there is no self-will; no thirst for earthly riches or for sensual pleasures; and from the cloister these pernicious desires, by means of the holy vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity, are effectually excluded. In heaven, to praise God is the constant occupation of the saints, and in religion every action of the Community is referred to the glory of His Name. "You praise God," says St. Augustine, "by the discharge of every duty; you praise Him when you eat or drink; you praise Him when you rest or sleep." You praise the Lord by regulating the affairs of the Monastery, by assisting in the sacristy or at the door; you praise the Lord when you go to table; you praise Him when you retire to rest and sleep; you praise Him in every action of your life. Lastly, in heaven the saints enjoy continual peace; because there they find in God the source of every good; and in religion, where God alone is sought, in Him is found that peace which surpasses all understanding, and that content which the world cannot give.

Well, then, might St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi say that the spouse of Jesus should have a high esteem and veneration for his holy state, since after baptism a vocation to religion is the greatest grace which God can bestow. You, then, who are religious should hold the religious state in higher estimation than all the dignities and kingdoms of the earth. In that holy state you are preserved from sins which you would commit in the world; there you are constantly occupied in holy exercises; there you meet every day with numberless opportunities of meriting an eternal crown. In this life religion makes you the spouse of a God, and in the next will raise you to the rank of prince in the eternal kingdom of his glory. How did you merit to be called to that holy state, in preference to so many others who had stronger claims than you? Black, indeed, must be your ingratitude if, for the benefit of your vocation, you do not thank God every day with all the affections of your soul.

Advantages of the Religious State according to St. Bernard.

The advantages of the religious state cannot be better described than in the words of St. Bernard: "Is not that a holy state in which a man lives more purely, falls more rarely, rises more speedily, walks more cautiously, is bedewed with the waters of grace more frequently, rests more securely, dies more confidently, is cleansed more quickly, and rewarded more abundantly?"

Vivit purius. — "A religious lives more purely."

Surely all the works of religious are in themselves most pure and acceptable before God. Purity of action consists principally in purity of intention, or in a pure motive of pleasing God. Hence our actions will be agreeable to God in proportion to their conformity to His Holy Will, and to their freedom from the corruption of self-will. The actions of a secular, however holy and fervent he may be, partake more of self-will than those of religious. Seculars pray, communicate, hear Mass, read, take the discipline, and recite the Divine Office when they please. But a religious performs these duties at the time prescribed by obedience — that is by the Holy Will of God. For in his Rule and in the commands of his Superior he hears His voice. Hence a religious, by obedience to his Rule and to his Superior, merits an eternal reward, not only by his prayers and by the performance of his spiritual duties, but also by his labours, his recreations, and attendance at the parlour; by his meals, his amusements, his words, and his repose. For, since the performance of all these duties is dictated by obedience, and not by self-will, he does in each the Holy Will of God, and by each he earns an everlasting crown.

Oh! how often does self-will vitiate the most holy actions? Alas! to how many, on the day of judgment, when they shall ask, in the words of Isaias, the reward of their labours, "Why have we fasted, and thou hast not regarded? — have we humbled our souls, and thou hast not taken notice" (Is. 58:3) — to how many, I say, will the Almighty Judge answer, Behold, in the day of your fast, your own will is found.(Is. 58:3) What! He will say, do you demand a reward? Have you not, in doing your own will, already received the recompense of your toils? Have you not, in all your duties, in all your works of penance, sought the indulgence of your own inclinations, rather than the fulfilment of My Will?

Abbot Gilbert says that the meanest work of a religious is more meritorious in the sight of God than the most heroic action of a secular. St. Bernard asserts that if a person in the world did the fourth part of what is ordinarily done by religious, he would be venerated as a saint. And has not experience shown that the virtues of many whose sanctity shone resplendent in the world faded away before the bright examples of the fervent souls whom, on entering religion, they found in the cloister? A religious, then, because in all his actions he does the Will of God, can truly say that he belongs entirely to Him. The Venerable Mother Mary of Jesus, foundress of the convent of Toulouse, used to say that for two reasons she entertained a high esteem for her vocation: first, because a religious enjoys the society of Jesus Christ, who, in the Holy Sacrament, dwells with Him in the same habitation; secondly, because a religious having by the vow of obedience sacrificed his own will and his whole being to God, he belongs unreservedly to Him.

Cadit rarius. "A religious falls more rarely."

Religious are certainly less exposed to the danger of sin than seculars. Almighty God represented the world to St. Anthony, and before him to St. John the Evangelist, as a place full of snares. Hence, the holy Apostle said, that in the world there is nothing but the concupiscence of the flesh, or of carnal pleasures; the concupiscence of the eyes, or of earthly riches and the pride of life,(1 Jn. 2:16) or worldly honours, which swell the heart with petulance and pride. In religion, by means of the holy vows, these poisoned sources of sin are cut off. By the vow of chastity all the pleasures of sense are forever abandoned; by the vow of poverty the desire of riches is perfectly eradicated; and by the vow of obedience the ambition of empty honours is utterly extinguished.

It is, indeed, possible for a Christian to live in the world without any attachment to its goods; but it is difficult to dwell in the midst of pestilence and to escape contagion. The whole world, says St. John, is seated in wickedness. (1 Jn. 5:19) St. Ambrose, in his comment on this passage, says, that they who remain in the world live under the miserable and cruel despotism of sin. The atmosphere of the world is noxious and pestilential. whosoever breathes it, easily catches spiritual infection. Human respect, bad example, and evil conversations are powerful incitements to earthly attachments and to estrangement of the soul from God. Everyone knows that the damnation of numberless souls is attributable to the occasions of sin so common in the world. From these occasions religious who live in the retirement of the cloister are far removed. Hence St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi was accustomed to embrace the walls of her convent, saying, "O blessed walls! O blessed walls! from how many dangers do you preserve me." Hence, also, Blessed Mary Magdalene of Orsini, whenever she saw a religious laugh, used to say: Laugh and rejoice, dear Sister, for you have reason to be happy, being far away from the dangers of the world."

Surgit velocius. — "A religious rises more speedily."

If a religious should be so unfortunate as to fall into sin, he has the most efficacious helps to rise again. His Rule which obliges him to frequent the holy sacrament of penance; his meditations, in which he is reminded of the eternal truths; the good examples of his saintly companions, and the reproofs of his Superiors, are powerful helps to rise from his fallen state. Woe, says the Holy Ghost, to him that is alone; for when he falleth he hath none to lift him up. (Eccles. 4:10) If a secular forsake the path of virtue, he seldom finds a friend to admonish and correct him, and is therefore exposed to great danger of persevering and dying in his sins. But in religion, if one fall he shall be supported by the other.(Ibid) If a religious commit a fault, his companions assist him to correct and repair it. "He," says St. Thomas, "is assisted by his companions to rise again."

Incedit cautius. — "A religious walks more cautiously."

Religious enjoy far greater spiritual advantages than the first princes or monarchs of the earth. Kings, indeed, abound in riches, honours, and pleasures, but no one will dare to correct their faults, or to point out their duties. All abstain from mentioning to them their defects, through fear of incurring their displeasure; and to secure their esteem many even go so far as to applaud their vices. But if a religious go astray, his error will be instantly corrected; his Superiors and companions in religion will not fail to admonish him, and to point out his danger, and even the good example of his Brothers will remind him continually of the transgression into which he has fallen. Surely a Christian, who believes that eternal life is the one thing necessary, should set a higher value upon these helps for salvation than upon all the dignities and kingdoms of the earth.

As the world presents to seculars innumerable obstacles to virtue, so the cloister holds out to religious continual preventives of sin. In religion, the great care which is taken to prevent light faults is a strong bulwark against the commission of grievous transgressions. If a religious resist temptations to venial sin, he merits by that resistance additional strength to conquer temptations to mortal sin; but if, through frailty, he sometimes yields to them, all is not lost—the evil is easily repaired. Even then the enemy does not get possession of his soul; at most he only succeeds in taking some unimportant outpost, from which he may be easily driven; while by such defeats the religious is taught the necessity of greater vigilance and of stronger defences against future attacks. He is convinced of his own weakness, and being humbled and rendered diffident of his own powers, he recurs more frequently, and with more confidence, to Jesus Christ and His Holy Mother. Thus, from these falls, the religious sustains no serious injury; since, as soon as he is humbled before the Lord, He stretches forth His All-Powerful Arm to raise him up. When he shall fall he shall not be bruised, for the Lord putteth his hand under him (Ps. 36:24). On the contrary, such victories over his weakness contribute to inspire greater diffidence in himself, and greater confidence in God. Blessed Egidius, of the Order of St. Francis, used to say that one degree of grace in religion is better than ten in the world; because in religion it is easy to profit by grace and hard to lose it, while in the world grace fructifies with difficulty and is lost with facility.

Irroratur frequentius. — "A religious is bedewed more frequently."

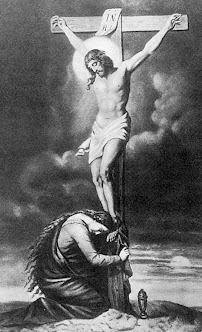

O God, with what internal illuminations, spiritual delights, and expressions of love does Jesus refresh His spouses at prayer, Communion, in presence of the Holy Sacrament, and in the cell before the crucifix! Christians in the world are like plants in a barren land, on which but little of the dew of heaven falls, and from that little the soil for want of proper cultivation seldom derives fertility. Poor seculars! They desire to devote more time to prayer, to receive the Holy Eucharist, and to hear the Word of God more frequently; they long for greater solitude, for more recollection, and a more intimate union of their souls with God. But temporal affairs, human ties, visits of friends, and restraints of the world place these means of sanctification almost beyond their reach. But religious are like trees planted in a fruitful soil, which is continually and abundantly watered with the dews of heaven. In the cloister, the Lord continually comforts and animates his spouses by infusing interior lights and consolations during the time of meditation, sermons, and spiritual readings, and even by means of the good example of their Brothers. Well, then, might Mother Catharine of Jesus, of the holy Order of St. Teresa, say, when reminded of the labours she had endured in the foundation of a convent: "God has rewarded me abundantly, by permitting me to spend one hour in religion, in the house of his Holy Mother."

Quiescit securius. — "A religious rests more securely."

Worldly goods can never satisfy the cravings of the human soul. The brute creation, being destined only for this world is content with the goods of the earth, but being made for God, man can never enjoy happiness except in the possession of the Divinity. The experience of ages proves this truth; for if the goods of this life could content the heart of man, kings and princes, who abound in riches, honours, and carnal pleasures, should spend their days in pure unalloyed bliss and felicity. But history and experience attest that they are the most unhappy and discontented of men; and that riches and dignities are always the fertile sources of fears, of troubles, and of bitterness. The Emperor Theodosius entered one day, unknown, into the cell of a solitary monk, and after some conversation said: "Father do you know who I am? I am the Emperor Theodosius." He then added: "Oh! how happy are you, who lead here on earth a life of contentment, free from the cares and woes of the world. I am a Sovereign of the earth, but be assured, Father, that I never dine in peace."

But how can the world, a place of treachery, of jealousies, of fears and commotions, give peace to man? In the world indeed, there are certain wretched pleasures which perplex rather than content the soul; which delight the senses for a moment, but leave lasting anguish and remorse behind. Hence the more exalted and honourable the rank and station a man holds in the world, the greater is his uneasiness and the more racking his discontent; for earthly dignities, in proportion to their elevation, are accompanied with cares and contradictions. We may, then, conclude that the world, in which the heart-rending passions of ambition, avarice, and the love of pleasures, exercise a cruel tyranny over the human race, must be a place not of ease and happiness, but of inquietude and torture. Its goods can never be possessed in such a way that they may be had in the manner and at the time we desire their possession; and when enjoyed, instead of infusing content and peace into the soul, they drench it with the bitterness of gall. Hence, whosoever is satiated with earthly goods, is saturated with wormwood and poison.

Happy, then, the religious who loves God, and knows how to estimate the favor which he bestowed upon him in calling him from the world and placing him in religion; where conquering, by holy mortification, his rebellious passions, and practising continual self-denial, he enjoys that peace which, according to the Apostle, exceeds all the delights of sensual gratification: The peace of God, which surpasseth all understanding! (Phil. 4:7) Find me, if you can, among those seculars on whom fortune has lavished her choicest gifts, or even among the first princes or kings of the earth, a soul more happy or content than a religious divested of every worldly affection, and intent only on pleasing God? He is not rendered unhappy by poverty, for He preferred it before all the riches of the earth; he has voluntarily chosen it, and rejoices in its privations; nor by the mortification of the senses, for he entered religion to die to the world and to himself; nor by the restraints of obedience, for he knows that the renunciation of self-will is the most acceptable sacrifice he could offer to God. He is not afflicted at his humiliations, because it was to be despised that he came into the house of God. I have chosen to be an abject in the house of my God, rather than dwell in the tabernacles of sinners! (Ps. 33:11) The enclosure is to her rather a source of consolation than of sorrow; because it frees him from the cares and dangers of the world. To serve the Community, to be treated with contempt, or to be afflicted with infirmities, does not trouble the tranquillity of his soul, because he knows that all these make him more dear to Jesus Christ. Finally, the observance of his Rule does not interrupt the joy of a religious, because the labours and burdens which it imposes, however numerous and oppressive they may be, are but the wings of the dove which are necessary to fly towards God and be united with him. Oh! how happy and delightful is the state of a religious whose heart is not divided, and who can say with St. Francis: "My God and my all."

It is true that even in the cloister, there are some discontented souls; for even in religion there are some who do not live as religious ought to live. To be a good religious and to be content are one and the same thing; for the happiness of a religious consists in a constant and perfect union of his will with the adorable Will of God. Whosoever is not united with him cannot be happy; for God cannot infuse his consolations into a soul that resists his Divine Will. I have been accustomed to say, that a religious in his monastery enjoys a foretaste of paradise or suffers an anticipation of hell. To endure the pains of hell is to be separated from God; to be forced against the inclinations of nature to do the will of others, to be distrusted, despised, reproved, and chastised by those with whom we live; to be shut up in a place of confinement, from which it is impossible to escape; in a word, it is to be in continual torture without a moment's peace. Such is the miserable condition of a bad religious; and therefore he suffers on earth an anticipation of the torments of hell. The happiness of paradise consists in an exemption from the cares and afflictions of the world, in the conversations of the saints, in a perfect union with God, and the enjoyment of continual peace in God. A perfect religious possesses all these blessings, and therefore receives in this life a foretaste of paradise.

The perfect spouses of Jesus have, indeed their crosses to carry here below; for this life is a state of merit, and consequently of suffering. The inconveniences of living in Community are burdensome; the reproofs of Superiors, and the refusals of permission, galling; the mortification of the senses, painful, and the contradiction and contempt of companions, intolerable to self-love. But to a religious who desires to belong entirely to God all these occasions of suffering are so many sources of consolation and delight, for he knows that by embracing pain he offers a sweet odour to God. St. Bonaventure says that the love of God is like honey, which sweetens everything that is bitter. The Venerable Cæsar da Bustis addressed a nephew who had entered religion in the following words: "My dear nephew, when you look at the heavens, think of paradise; when you see the world, reflect on hell, where the damned endure eternal torments without a moment's enjoyment when you behold your monastery, remember purgatory, here many just souls suffer in peace and with a certainty of eternal life." And what more delightful than to suffer (if suffering it can be called) with a tranquil conscience? than to suffer in favour with God, and with an assurance that every pain will one day become a gem in an everlasting crown? Ah! the brightest jewels in the diadems of the saints are the sufferings which they endured in this life with patience and resignation.

Our God is faithful to His promises, and grateful beyond measure. He knows how to remunerate His servants, even in this life, by interior sweetness, for the pains which they patiently suffer for his sake. Experience shows that religious who seek consolation and happiness from creatures are always discontented, while they who practise the greatest mortifications enjoy continual peace. Let us, then, be persuaded that neither pleasures of sense, nor honours, nor riches, nor the world with all its goods can make us happy. God alone can content the heart of man. Whoever finds Him possesses all things. Hence St. Scholastica said, that if men knew the peace which religious enjoy in retirement, the entire world would become one great convent, and St. Mary Magdalene be Pazzi used to say that they would abandon the delights of the world and force their way into religion. Hence, also St Laurence Justinian says that "God has designedly concealed the happiness of the religious state, because if it were known all would relinquish the world and fly to religion."

The very solitude, silence, and tranquillity of the cloister give to a soul that loves God a foretaste of paradise. Father Charles of Lorraine, a Jesuit of royal extraction, used to say that the peace which he enjoyed during a single moment in his cell was an abundant remuneration for the sacrifice that he had made in quitting the world. Such was the happiness which he occasionally experienced in his cell, that he would sometimes exult and dance with joy. Blessed Seraphino of Ascoli, a Capuchin, was in the habit of saying that he would not give one foot of his cord for all the kingdoms of the earth. Arnold, a Cistercian, comparing the riches and honours of the court which he had left with the consolations which he found in religion, exclaimed "How faithfully fulfilled, O Jesus, is the promise which Thou didst make of rendering a hundred-fold to him who leaves all things for Thy sake!" St. Bernard's monks, who led lives of great penance and austerities, received in their solitude such spiritual delights, that they were afraid they should obtain in this life the reward of their labours.

Let it be your care to unite yourself closely to God; to embrace with peace all the crosses that He sends you; to love what is most perfect; and, when necessary, to do violence to yourself. And that you may be able to accomplish all this, pray continually; pray in your meditations, in your Communions, in your visits to the Blessed Sacrament, and especially when you are tempted by the devil; and you will obtain a place in the number of those fervent souls who are more happy and content than all the princes and Kings and emperors of the earth.

Beg of God to give you the spirit of a perfect religious; that spirit which impels the soul to act, not according to the dictates of nature, but according to the motions of grace, or from the sole motive of pleasing God. Why wear the habit of a religious, if in heart and soul you are a secular, and live according to the maxims of the world? Whosoever profanes the garb of religion by a worldly spirit and a worldly life has an apostate heart. "To maintain," says St. Bernard, "a secular spirit under the habit of religion, is apostasy of heart." The spirit of a religious, then, implies an exact obedience to the rules and to the directions of the Superior, along with a great zeal for the interests of religion. Some religious wish to become saints, but only according- to their own caprice; that is, by long silence, prayer, and spiritual reading, without being employed in any of the offices of the Community. Hence, if they are sent to the parlour, to the door, or to other distracting occupations, they become impatient; they complain and sometimes obstinately refuse to obey, saying that such offices are to them occasions of sin. Oh! such is not the spirit of religious. Surely what is conformable to the Will of God cannot hurt the soul. The spirit of a religious requires a total detachment from commerce with the world; great love and affection for prayer, for silence, and for recollection; ardent zeal for exact observance; deep abhorrence for sensual indulgence; intense charity towards all men; and, finally, a love of God capable of subduing and of ruling all the passions. Such is the spirit of a perfect religious. Whosoever does not possess this spirit should at least desire it ardently, should do violence to himself, and earnestly beg God's assistance to obtain it. In a word, the spirit of a religious supposes a total disengagement of the heart from everything that is not God, and a perfect consecration of the soul to Him, and to Him alone.

Moritur confidentius. — "A religious dies more confidently."

Some are deterred from entering religion by the apprehension that their abandonment of the world might be afterwards to them a source of regret. But in making choice of a state of life I would advise such persons to reflect not on the pleasures of this life, but on the hour of death, which will determine their happiness or misery for all eternity. And I would ask if, in the world, surrounded by seculars, disturbed by the fondness of children, from whom they are about to be separated forever, perplexed with the care of their worldly affairs, and disturbed by a thousand scruples of conscience, they can expect to die more contented than in the house of God, assisted by their holy companions, who continually speak of God; who pray for them, and console and encourage them in their passage to eternity? Imagine you see, on the one hand, a prince dying in a splendid palace, attended by a retinue of servants, surrounded by his wife, his children, and relatives, and represent to yourself, on the other, a religious expiring in his convent, in a poor cell, mortified, humble; far from her relatives, stripped of property and self-will; and tell me, which of the two, the rich prince or the poor brother, dies more contented? Ah! the enjoyment of riches, of honours, and pleasures in this life do not afford consolation at the hour of death, but rather beget grief and diffidence of salvation; while poverty, humiliations penitential austerities and detachment from the world render death sweet and amiable, and give to a Christian increased hopes of attaining that true felicity which shall never terminate.

Jesus Christ has promised that whosoever leaves his house and relatives for God's sake shall enjoy eternal life. And every one that hath left house or brethren, or sisters, or father, or mother, or lands for my sake shall receive a hundredfold, and shall possess life everlasting. (Mt.19:29) A certain religious, of the Society of Jesus, being observed to smile on his death-bed, some of his brethren who were present began to apprehend that he was not aware of his danger, and asked him why he smiled; he answered: "Why should I not smile, since I am sure of paradise? Has not the Lord himself promised to give eternal life to those who leave the world for His sake? I have long since abandoned all things for the love of Him: He cannot violate His own promises. I smile, then, because I confidently expect eternal glory." The same sentiment was expressed long before by St. John Chrysostom, writing to a certain religious. "God," says the saint, "cannot tell a lie, but He has promised eternal life to those who leave the goods of this world. You have left all these things; why, then, should you doubt the fulfilment of His promise?"

St Bernard says that "it is very easy to pass from the cell to heaven; because a person who dies in the cell scarcely ever descends into hell since it seldom happens that a religious perseveres in his cell till death, unless he be predestined to happiness." Hence St. Laurence Justinian says that religion is the gate of paradise; because living in religion, and partaking of its advantages is a great mark of election to glory. No wonder, then, that Gerard, the brother of St. Bernard, when dying in his monastery, began to sing with joy and gladness. God Himself says: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord. (Apoc. 14:19) And surely religious who by the holy vows, and especially by the vow of obedience, or total renunciation of self-will, die to the world and to themselves must be ranked amongst the number of those who die in the Lord. Hence Father Suarez, remembering at the hour of death that all his actions in religion were performed through obedience, was filled with spiritual joy, and exclaimed that he could not imagine death could be so sweet and so full of consolation.

Purgatur citius. — "A religious is cleansed (in purgatory) more quickly."

St. Thomas teaches that the perfect consecration which a religious makes of himself to God by his solemn profession remits the guilt and punishment of all his past sins. "But," he says, "it may reasonably be said that a person by entering into religion obtains the remission of all sins. For, to make satisfaction for all sins, it is sufficient to dedicate one's self entirely to the service of God by entering religion, which dedication exceeds all manner of satisfaction. Hence," he concludes, "we read in the lives of the Fathers, that they who enter religion obtain the same grace as those who receive baptism." The faults committed after profession by a good religious are expiated in this world by his daily xercises of piety, by his meditations, Communions, and mortifications. But if a religious should not make full atonement in this life for all his sins, his purgatory will not be of long duration. The many sacrifices of the Mass which are offered for him after death, and the prayers of the Community, will soon release him from his suffering.

Remuneratur copiosius. — "A religious is more abundantly rewarded."

Worldlings are blind to the things of God; they do not comprehend the happiness of eternal glory, in comparison with which the pleasures of this world are but wretchedness and misery. If they had just notions, and a lively sense of the glory of paradise, they would assuredly abandon their possessions, even kings would abdicate their crowns,—and, quitting the world, in which it is exceedingly difficult to attend to the one thing necessary, they would retire into the cloister to secure their eternal salvation. Bless, then, dear Brother, and continually thank your God, who, by His own lights and graces, has delivered you from the bondage of Egypt, and brought you to His own house; prove your gratitude by fidelity in His service, and by a faithful correspondence to so great a grace. Compare all the goods of this world with the eternal felicity which God has prepared for those who leave all things for His sake, and you will find that there is a greater disparity between the transitory joys of this life and the eternal beatitude of the saints than there is between a grain of sand and the entire creation.

Jesus Christ has promised that whosoever shall leave all things for His sake shall receive a hundred-fold in this life, and eternal glory in the next. Can you doubt His words? Can you imagine that He will not be faithful to His promise? Is He not more liberal in rewarding virtue than in punishing vice? If they who give a cup of cold water in His Name shall not be left without abundant remuneration, how great and incomprehensible must be the reward which a religious who aspires to perfection shall receive for the numberless works of piety which he performs every day? — for so many meditations, offices, and spiritual readings? — for so many acts of mortification and of divine love which he daily refers to God's honour? Do you not know that these good works which are performed through obedience, and in compliance with the religious vows, merit a far greater reward than the good works of seculars? Brother Lacci, of the Society of Jesus, appeared after death to a certain person, and said that he and King Philip II were crowned with bliss, but that his own glory as far surpassed that of Philip as the exalted dignity of an earthly sovereign is raised above the lowly station of an humble religious.

The dignity of martyrdom is sublime; but the religious state appears to possess something still more excellent. The martyr suffers that he may not lose his soul; the religious, to render himself more acceptable to God. A martyr dies for the Faith, a religious for perfection. Although the religious state has lost much of its primitive splendour, we may still say, with truth, that the souls who are most dear to God, who have attained the greatest perfection, and who edify the Church by the odour of their sanctity, are, for the most part, to be found in religion. I hold as certain that the greater number of the seraphic thrones vacated by the unhappy associates of Lucifer will be filled by religious. Out of the sixty who during the last century were enrolled in the catalogue of saints, or honoured with the appellation of Blessed, all, with the exception of five or six, belonged to the religious orders. Jesus Christ once said to St. Teresa: "Woe to the world, but for religious." Ruffinus says: "It cannot be doubted that the world is preserved from ruin by the merits of religious." When, then, the devil affrights you by representing the difficulty of observing your Rule, and practising the self-denial, and the austerities necessary for salvation, raise your eyes to heaven, and the hope of eternal beatitude will give you strength and courage to suffer all things. The trials, mortifications, and all miseries of this life will soon be past, and to them will succeed the ineffable delights of paradise, which shall be enjoyed for eternity without fear of failure or of diminution.

O God of my soul, I know that Thou dost most earnestly desire to save me. By my sins I had incurred the sentence of eternal condemnation but instead of casting me into hell, as I deserved, Thou hast stretched forth Thy loving hand, and not only delivered me from hell and sin, but Thou hast also drawn me, as it were by force, from amidst the dangers of the world, and placed me in Thy own house amongst Thy own spouses. I hope, O my Spouse, to be admitted one day to heaven, there to sing for eternity the great mercies Thou hast shown me. Oh! that I had never offended Thee. O Jesus, assist me, now that I desire to love Thee with my whole soul, and wish to do everything in my power to please Thee. Thou hast spared nothing in order to gain my love: it is but just that I devote my entire being to Thy service. Thou hast given thyself entirely to me. I give myself without reserve to Thee. Since my soul is immortal, I desire to be eternally united to Thee. And if it is love that unites the soul to Thee, I love Thee, O my Sovereign Good I love Thee, my Redeemer ; I love Thee, O my Spouse, my only treasure and object of my love: I love Thee! I love Thee! and hope that I shall love Thee for eternity. Thy merits, O my Redeemer, are the grounds of my hope. In Thy protection, also, O great Mother of God, my Mother Mary, do I place unbounded confidence. Thou didst obtain pardon for me when I was in the state of sin; now that I hope I am in the state of grace, and am a religious, wilt thou not obtain for me the grace to become a saint? Such is my ardent hope, my fervent desire. Amen.