The Two Marks of a Religious Vocation

IntroductionWhen a King levies soldiers to make war, his foresight and prudence require, that he should prepare weapons to arm them; for what sense would there be in sending them to fight without arms. If he did so, he would be taxed with great imprudence.

St. Bernardine of Siena,

Bishop and Doctor of the Church.

Now God acts in the same way. “He does not call,” says St Bernadine of Sienna, “without giving, at the same time, to those whom He calls, all that is required to accomplish the end for which He calls.”

So that when God calls a person to religion, He furnishes him with the physical, intellectual, and moral qualities necessary for the religious life. In other words, God not only gives him the inclination but He also endows him with the ability for the performance of the duties of that state of life.

MARK I.

THE ABILITY

FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF

THE DUTIES OF RELIGIOUS LIFE.

As regards ability, the physical constitution of the postulant should be such as to aid, rather than prevent, the development of his intellectual and moral faculties; it should be sufficiently strong to endure the hardships of the religious life; and it should, moreover, be free from any hereditary disease.

The mind of the postulant should be calm and deliberate; it should be strong, so as to be able to apply, if required, to study, or to many spiritual exercises, without danger of being deranged. Weak minds will always be in danger of derangement from much mental application.

This danger is so much the more to be apprehended, if, at the same time, these persons are of very nervous temperament, or of a rather scrupulous conscience, or if they are bound to fast too much, of if they have led for a time, a very sinful life; on account of which they will, on the ordinary course of Providence, sooner or later have to suffer many great temptations which will bring upon them many hard mental afflictions and combats which weak minds cannot endure long.

Less mind, more judgmentWith regard to the intellectual faculties, the postulant need not have talents so brilliant as to make him a great mind; but he should have a sound, practical judgment, that is, common sense. “Moins d’esprit, plus de jugement - Less mind, more judgment,” as the French say.

Neither great talents for some certain branches of science, nor piety and the spirit of devotion can make up for deficiency of judgment or common sense. Subjects of medium talents, yet gifted with a sound, practical judgment are generally the best suited for Religious Communities, because they are humble and docile.

St. Vincent de Paul,

Founder of the Congregation of the Mission.

“Men of superior talents,” says St Vincent de Paul, “not possessing at the same time an unusual disposition to advance in virtue, are not good for us; for no solid virtue can take root in self-conceited, and self-willed souls.”

St. Francis de Sales

Bishop and Doctor of the Church.

In reference to the intellectual faculties of the postulant, St Francis de Sales expresses himself thus: “If I say that, in order to become a religious, one should have a good mind, I do not mean those great geniuses, who are generally vain and self-conceited, and in the world are but receptacles of vanity. Such men do not embrace the religious life to humble themselves, but to govern others, and direct everything according to their own views and inclinations, as if the object of their entrance into religion was to be lecturers in philosophy and theology.”

St. Jane Frances de Chantal

St. Jane Frances de Chantal,

Foundress of the Order of the Visitation.“These great minds,” says St Jane Frances de Chantal in one of her letters, “when they are not given to devotion, submission and mortification, serve to ruin a whole religious community, nay even a whole religious Order.” “We must pay special attention to these,” says St Francis de Sales, “I do not say they should not be received, but I do say, that we should be very cautious about them; for in time and by God’s grace, they may greatly change; and this will undoubtedly come to pass, if they are faithful in making use of those means which are given them for their cure.

Regulated and sensible

“When therefore I speak of a good mind, I mean well regulated and sensible minds, and also those of moderate powers, which are neither too great, nor too little; for such minds always do a great deal without knowing it; they set themselves to labour with a good intention, and give themselves to the practise of solid virtue. They are tractable, and allow themselves to be governed without much trouble; for they easily understand how good a thing it is to let themselves be guided.”

“Good minds,” says St Frances de Chantal, “are always capable of the religious observances, whilst the weak are liable to relaxation. Believe me, dear Sisters, I conjure you, to look well at the natural dispositions of those whom you receive; for I know, that nature ever remains, and will, every now and then, burst forth. There are very few who dispose themselves to receive sufficient grace to overcome a bad natural disposition, and rarely do we see a person of good mind and good disposition perverted.”

Moral qualities

As to the moral qualities of the postulant, they should be such as to suit a life in common. Hence he should easily agree with, and yield to, others, and be of a cheerful, happy, gay, affable and social disposition. St Francis de Sales says: “He should have a good heart, desiring to live in subjection and obedience.”

Pope Pius VII.

Pope Pius VII.Cardinal Wiseman says in his book on Pius VII: “If one sees the youthful aspirants to the religious institutes here or abroad, in recreation or at study, he may easily decide who will persevere by a very simple rule. The joyous faces and the sparkling eyes denote the future monks far more surely than the demure looks and stolen glances.”

MARK II.

THE INCLINATION

TO RELIGIOUS LIFE.

There are many thus far qualified, but, for all that, they are not called to religion, unless they experience at the same time an inclination for the religious life.

Now this inclination is nothing else than the firm and constant will to serve God in the manner and in the place to which His Divine Majesty calls him.

In many, the will is so inflamed with the love of the religious life, that they embrace it without any question about it and with exceedingly great pleasure.

In others, and perhaps the greater part of those who are called to religion, this love or inclination for the religious state is not so strong, but their understanding is so much enlightened by the grace of God, that they discover the vanity and dangers of this world, seeing also clearly, at the same time, the quiet, the safety, the happiness, in a word, the inestimable treasures of a religious life, though perhaps, as I have just said, somewhat dull in their affection, and not so ready to follow that which reason shows them.

This latter manner of inclination or love for the religious life is better than the former, and is more generally approved by those who are experienced in these matters, than the other which consists only in a fervent motion of the will; for being grounded in the light of reason and faith, it is less subject to error, and more likely to last.

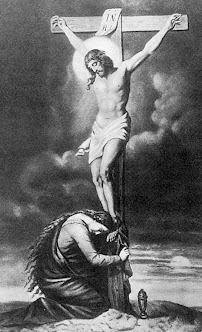

St Francis de Sales

giving the Rules of the Visitation Order

to St Jane Frances de Chantal.

Now in the opinion of St Francis de Sales, this firm and constant will of a person to serve God in the manner and in the place where God calls him, is the best mark of a religious vocation.

- “But observe,” adds this enlightened Saint,

- that when I say a firm and constant will of serving God,

- I do not say, that a person should from the beginning,

- perform everything required of his vocation,

- and that he should be perfect at once,

- and never feel tempted,

- unsettled,

- unshaken in his undertaking;

- I do not say,

- that he should never experience any doubts as to his religious calling,

- or should not waver, at times, in a kind of irresolution about his vocation:

- for this may happen from the weakness and repugnance of human nature,

- and the temptations of the devil, the arch-enemy of all good.

- Oh no! That is not what I mean to say;

- for every one is more or less subject

- to passions,

- changes and

- vicissitudes;

- and a person will love one thing today,

- and another thing tomorrow.

- No two days of our life are alike. Today is different from yesterday, and tomorrow will be unlike either.

- It is not, then, by these different movements and feelings that we ought to judge of the firmness and constancy of the will,

- but we should consider rather,

- whether amid this variety of movements,

- the will remains firm and unshaken,

- so as not to give up the good it has embraced;

- so that to have a mark of a good vocation,

- we do not need sensible constancy;

- but a constancy which is in the superior part of the soul,

- and which is effective."

Therefore, in order to know whether God calls us to religion, - we must not wait for Him

- to speak to us sensibly,

- nor to send us an Angel from Heaven to make known to us His will;

- still less do we need to have revelations on this subject;

- nor do we require an examination by ten or twelve divines to ascertain whether the inspiration be good or bad; whether we ought to follow it or not;

- but

- we ought to correspond to it well,

- and cultivate the first movements of grace,

- and then not to distress ourselves if disgusts or coldness arise concerning it;

- for

- if we always strive to keep our will very firm in the determination of seeking the good which is shown us,

- God will not fail to make all turn out well to His Glory.

- Such a will is found in those young persons who,

- quietly and with consideration,

- prepare themselves for their retreat from the world,

- by trying to be given more to

- patience,

- prayer,

- penance,

- fasting

- and the frequent reception of the sacraments.

- They are in earnest about the affair, and do not play, or if they do, it is at a good game, in which they can only be gainers. They will not act as Lot s wife, who looked back, nor as the children of Israel, who longed for the flesh-pots of Egypt.”

“To find this good will,” writes St Frances de Chantal in one of her letters,

- “we must inquire of the postulant, how he has profited by the desire of embracing the religious life, that is,

- whether he has been more fervent in approaching the sacraments,

- and reading pious books;

- in drawing his affections from the world;

- in becoming more meek in his conversations,

- and more obedient to his parents,

- and similar things.”

On the contrary,

- if young persons were mentioned to St Francis de Sales, who before their entrance into religion,

- gave themselves up to the vanities and pleasures of the world,

- to take - to use their own expression - a last farewell,

- he considered their call to religion very doubtful.

- When it was mentioned to him that they only retrograded a little, in order to take a fresh and better start, he replied,

- “that they might easily go back too far, and then make such a violent start as would make them lose breath, before they could come to take the leap. Experience teaches, that such characters seldom persevere through the year of probation, because any one who thus abuses and trifles with the grace of a religious vocation deserves to lose it.”

All things in Him Who strengthens me

When the austerities and trials of religious life have been fully represented to a postulant;

when his admittance has been delayed,

discouraged,

nay even refused for the sake of trial,

and he still perseveres in his entreaties to be received into the Order,

saying with St Paul, “I can do all things in Him Who strengthens me”:

such a postulant may also be considered to have a good and firm will

and a true vocation to the religious life.

Those who in order to become religious, make great sacrifices,

or suffer patiently unjust contradictions and ill treatment from their friends,

should be considered to have a true call.

When St Columban was on the point of carrying out his resolution of entering into religion, his mother threw herself across the threshold to obstruct his passage; but he courageously stepped over her, and hastened to the place of his vocation.

“There are many persons,” says St Francis de Sales,

- “who feel the first inspirations to the religious life rather strongly;

- nothing appears difficult to them;

- they seem to be able to overcome all obstacles;

- but when they meet with these vicissitudes,

- and when these first feelings are not so sensible in the inferior part of their soul,

- they imagine that all is lost,

- and that they must give up everything;

- they will, and they will not.

- What they then feel is not sufficient to make them leave the world.

- ‘I should wish it,’ one of these persons will say,

- ‘but I do not know whether it is the will of God that I should be a religious,

- as the inspiration which I now feel does not seem to me strong enough.

- It is quite true that I have felt it more strongly than I do at this moment;

- but as it is not lasting, I do not think it is good.’

- Certainly when I meet with such souls,

- I am not astonished at this disgust and coolness;

- still less can I for that reason think that their vocation is not good.

- We must, in this case, take great pains to assist them,

- and teach them not to be surprised at these changes,

- but encourage them to remain firm in the midst of them.

- Well, I say to them, that is nothing;

- tell me, have you not felt in your heart the movement or inspiration to seek so great a good?

- ‘Yes’, they say; ‘it is very true but it has passed away directly.’

- Yes indeed, I answer, the force of the sentiment passed away, but not so entirely as not to leave in you some affection for the religious life.

- ‘Oh no!’ the person says; ‘for I always have a sort of feeling which makes me tender on that point; but what troubles me is, that I do not feel this inclination so strongly as would be required of such a resolution.’

- I answer them,

- that such persons must not be troubled

- about these sensible feelings,

- nor examine them too closely;

- that they must be satisfied with that constancy of their will,

- which in spite of all this does not lose the affection of its first design;

- that they must only be careful to cultivate it well,

- and to correspond with this first inspiration.

- Do not care, I say, from what quarter it comes;

- for God has many ways of calling His servants into His service.

All are not drawn by the same means

Although it be most desirable, and should be held as a general rule, that a person should embrace the religious life from the motive of securing better his own salvation and sanctification, or working more profitably for the salvation of others, and above all, for the pure intention of serving God more perfectly and of belonging to Him alone, yet it cannot be denied, that God does not draw all whom He calls to His service, by the same means.

- He sometimes makes use of preaching;

- sometimes of the reading of good books.

- Others have been called by the annoyance,

- disasters, and

- afflictions which came upon them in the world,

- which caused them to be disgusted with it and to abandon it.

St. Paul the First Hermit

clothed in a habit of palm leaves. St. Arsenius the Great.

St. Arsenius the Great. St Paul the Hermit, and St Arsenius the Great

withdrew into the desert to escape persecution.

St Paul the Simple

who became a hermit

on account of the unfaithfulness of his wife.

Fr. Nicholas Bobadilla

one of the First Companions of St. Ignatius.

- Nicholas Bobadilla, a poor student of Paris, often went to see St Ignatius Loyola, for the sake of relief in his temporal wants; but he soon felt attached to St Ignatius, and became one of his first and most zealous companions.

Blessed Bernard of Corlionewho, in trying to escape the hands of human justice,

Blessed Bernard of Corlionewho, in trying to escape the hands of human justice,

fell into those of Divine Mercy by joining the Capuchins as a Brother. Thomas Pounde of Beaumontfound his true vocation after being kicked by Queen Elizabeth I.

Thomas Pounde of Beaumontfound his true vocation after being kicked by Queen Elizabeth I.- Thomas Pounde of Beaumont, an English gentleman, during the Royal Festivities of Christmastide 1551, fell most awkwardly, while dancing at a ball of the queen. The queen, Elizabeth I, reportedly kicked him and said, "Rise, Sir Ox". Pounde, humiliated, replied "Sic transit gloria mundi - Thus passes the glory of the world;" and thenceforward retired from court life feeling highly offended and resolved to avenge himself on the world by quitting it. He became a Jesuit Laybrother and entered an active career of winning people to the Faith. Thomas Pounde suffered in different prisons and dungeons for nearly thirty years during the time of the religious persecution in England and died a holy death.

- There are even others whose motives for embracing the religious life were still worse.

Capuchin Fathers

Capuchin Fathers- I have heard on good authority, says St. Francis de Sales, that a gentleman of our age, distinguished in mind and person, and of good family, seeing some Capuchin Fathers pass by, said to the other noblemen who were with him, ‘I have a fancy to find out how these barefooted men live, and to go amongst them, not intending to remain there always, but only for three weeks or a month, so as to observe better what they do, and then mock and laugh at it afterwards with you.’ So he went and was received by the Fathers. But Divine Providence, Who made use of these means to withdraw him from the world, converted his wicked purpose into a good one; and he who thought to take in others, was taken in himself; for no sooner had he lived a few days with those good religious, than he was entirely changed. He persevered faithfully in his vocation and became a great servant of God.”

Blessed Margaret of Costello,

Blessed Margaret of Costello,

Dominican.Born a hunchback, dwarf, blind, and lame,

her family was ashamed of her and finally abandoned her.- There are again others who go into religion on account of some natural defect, for instance, because they are lame, or blind of one eye, or ugly, or have some other similar defect. Thus many enter religion through disgust or weariness, or on account of disappointments and troubles which detach them from the love of creatures; they preserve them from the delusion of false appearances, and force them to enter into themselves; they purify their hearts; they cause goodness to take root in their souls; they give them a distaste for life in the world.

Some souls are preserved from the delisions of the world,

and opened to the call of God,

through sorrow, disgust or social rejection.

- Would such souls have sought consolation only in God, if the world had loved them? Would they have known the sweetness of God, if the world had not maltreated and banished them from its society? It is God who permits such harsh treatment and refusals to befall them. He causes thorns to spring over all their pleasures, in order to prevent their reposing thereon. They would never have belonged to God, had the world desired them; and they would have been adverse to Him, had the world not been adverse to them. It is thus that the Lord breaks the fetters, by which the world held them in bondage.

“There are souls,” says St Francis de Sales, “who were the world to smile upon them, would never become religious; yet by means of contradictions and disappointments, they are brought to despise the vanities, and all allurements of the world, and understand its fallacy.”

“Our Lord has often made use of such means to call many persons to His service, whom He could not have otherwise. For although God is all-powerful and can do what He wills, yet He does not will to take away the liberty which He has given us; and when He calls us to His service, He will have us enter it willingly, and not by force or constraint.

Now, though these persons come to God, as it were,

- in anger against the world, which has displeased them, or

- on account of some troubles or

- afflictions which have tormented them,

- yet they do not fail to give themselves to God of their own free will; and very often such persons succeed very well in the service of God, and become great Saints, sometimes greater than those who have entered it with more evident vocations, or with far purer motives. God, very often in these cases, shows the greatness of His Wisdom and Divine Goodness.

- He draws good from evil by employing the intentions of these persons, which are by no means good in themselves, to make those persons, great servants of His Divine Majesty. Those whom the Gospel mentions as having been forced to partake of the feast, did not, on that account, relish it less.

“The Divine Artisan takes pleasure in making beautiful buildings with wood that is very crooked and has no appearance of being fit for anything; and, as a person who does not understand carpenter’s work, seeing some crooked wood in his shop, would be astonished to hear him say it was meant for making some fine work of art (for he would say, how often must the plane pass over it before it can be fit for such a work?)

So Divine Providence, usually makes masterpieces out of these crooked and sinister intentions. He makes the lame and blind come to His feast, to show us that we need not have two eyes or two feet to enter Paradise; that it is better to go to Heaven with one leg, one eye, or one arm, than to have two and be lost. Now this sort of people having entered religion in this way, have often been known to make great progress in virtue and persevere faithfully in their vocation.

Conclusion

1 It cannot be expected, that all should commence with perfection.

2 It matters little in what manner we begin, provided we are resolved to attain our end by strenuous efforts.

3 We must then revere and esteem the incomprehensible ways and inscrutable judgments of God, in this great variety of the vocations and means of which He makes use to draw His creatures to His service.

4 “Now, from this great multiplicity of vocations and variety of motives, it follows that it is often a difficult matter to form a correct judgment as to whether a person is called to a religious life. This difficulty, however, vanishes in a great measure, if we apply the mark given above, namely, that, among the several marks of a good vocation, the best and surest of them all is the firm and constant will to serve God in the manner and in the place to which one feels called by His Divine Majesty.”

5 The Inclination, then, for the religious life, implies not only the firm and constant will to serve God in religion in general, but it implies a particular attraction to a life either exclusively contemplative, or active or apostolico-monastic.

6 This attraction must be well inquired into, as it cannot be expected that a man will faithfully persevere in a manner of life, for which he feels no particular liking: it being almost impossible for human nature to go, for a lifetime, against a torrent.

Epilogue

Although ability and inclination, taken in the sense just explained, generally suffice to prove the religious vocation of a person, yet there are better and more evident marks than these, namely:

a. Divine Revelation. St Paul the Apostle, St. Alphonsus, St Aloysius Gonzaga, St Stanislaus, and others are examples of this kind.

b. Special Inspiration. By which a person is suddenly enlightened, and vehemently urged on to a life of perfection, and sweetly forced, as it were, thereto. These are extraordinary marks of vocation and, as such, are not included within the scope of this article. †

Read more...